How to pave the streets with gold

On pedestrianising Soho

Written by Joe Hill for the Greater London Project. Originally published in CityAM.

There is no consensus on how Soho got its name, but it has given it to many other districts across the world – there are Sohos (with varied spellings) as far afield as New York, Buenos Aires, Shanghai and Beijing. What started as a hunting ground gave way to farmland, then housing for the landed gentry, and began to resemble the modern-day entertainment district from the end of the 19th Century onwards.

Londoners and visitors from around the world value the area for its theatres, clubs, drinking and dining, and numerous entertainment and media businesses. But despite its central location and ease of access from across London, Soho is struggling.

During the pandemic, Westminster City Council allowed the area to be pedestrianised. They relaxed licensing rules and blocked off through-traffic so that cafes, bars and restaurants could let people dine ‘al fresco’ on tables lining the pavements. The scheme let businesses operate more than 16,000 additional ‘covers’ (sittings) across Westminster, supporting some 80,000 jobs in hospitality and saving countless businesses in Soho from going bust.

Since these measures were rolled back in 2021, businesses have been calling for them to be restored and made permanent. The Soho Business Alliance wrote to the Mayor asking for a pedestrianised Soho to be included in plans alongside the pedestrianisation of Oxford Street announced in September, in a move Westminster Council quickly condemned. The Mayor’s team have indicated that they don’t support the plan either, presumably because he would effectively be overruling the local Labour council, and it didn’t appear in their consultation on Oxford Street earlier this year.

But pedestrianising Soho is the right thing to do. London is an outlier in European cities when it comes to the lack of pedestrianised zones. Barcelona’s La Rambla, the rue des Rosiers in Paris, much of Madrid, and 50 hectares of Ghent in Belgium show us what designing urban areas around pedestrians, not vehicles, can do.

Streets clogged by cars, vans and motorbikes can be repurposed for pedestrians, tables and chairs for outdoor dining, and even smaller marketplaces. In enclosed and narrow spaces, the pollution from road traffic is terrible, hemmed in by tall buildings which have worse ventilation than open spaces or nearby parks. And London has something many of those cities lack – an excellent underground tube network running beneath its pavements, taking the pressure off of street-level public transport anyway.

The trouble is, until now Soho’s residents have so far been given an effective veto, and the vocal ones oppose the scheme. For some, it’s about wanting vehicle access. But for others, they just don’t see it as a good deal – trading the noise and pollution from occasional vehicles for the lack of access to their own cars, the noise of even more crowds and the litter that comes with them. Plenty will see it as a cost with no upside: homeowners can’t necessarily expect a bump in property value from a busier neighbourhood, and social housing residents wouldn’t share that incentive anyway. As with any city, the trade-off is between what local residents want, and the desires of everyone else.

Really, businesses in Soho shouldn’t have to appeal to a higher authority to try and get pedestrianisation. It should be in Westminster City Council’s interests to help grow local businesses, growing the revenues they can get from business rates in the long-run. But despite Westminster City Council being the biggest collector of business rate revenue in England, 96 per cent of that revenue is redistributed elsewhere. It goes to central government and other parts of the country, or the Mayor and other parts of London. And based on the Government’s proposals, even more of it is set to be redistributed in the future.

Although much of that funding still goes to services which the residents of Soho also need, such as Transport for London or the Metropolitan Police, it means the Council have negligible incentive to increase business rates revenue. It also gives the Council less room to ‘buy out’ local opposition with the proceeds of a richer and more prosperous Soho. More and more late opening licensing applications are being denied, yet more evidence that the Council isn’t incentivised to care about businesses being successful.

Fixing the incentives for London’s governments to care about business growth is a bigger problem. In the meantime, the centre of London isn’t just for residents, it’s also for everyone else. But at the moment, the rest don’t get a say about Soho’s future, and the system is set up to empower only a small but noisy group of local blockers. The Mayor can and should change that.

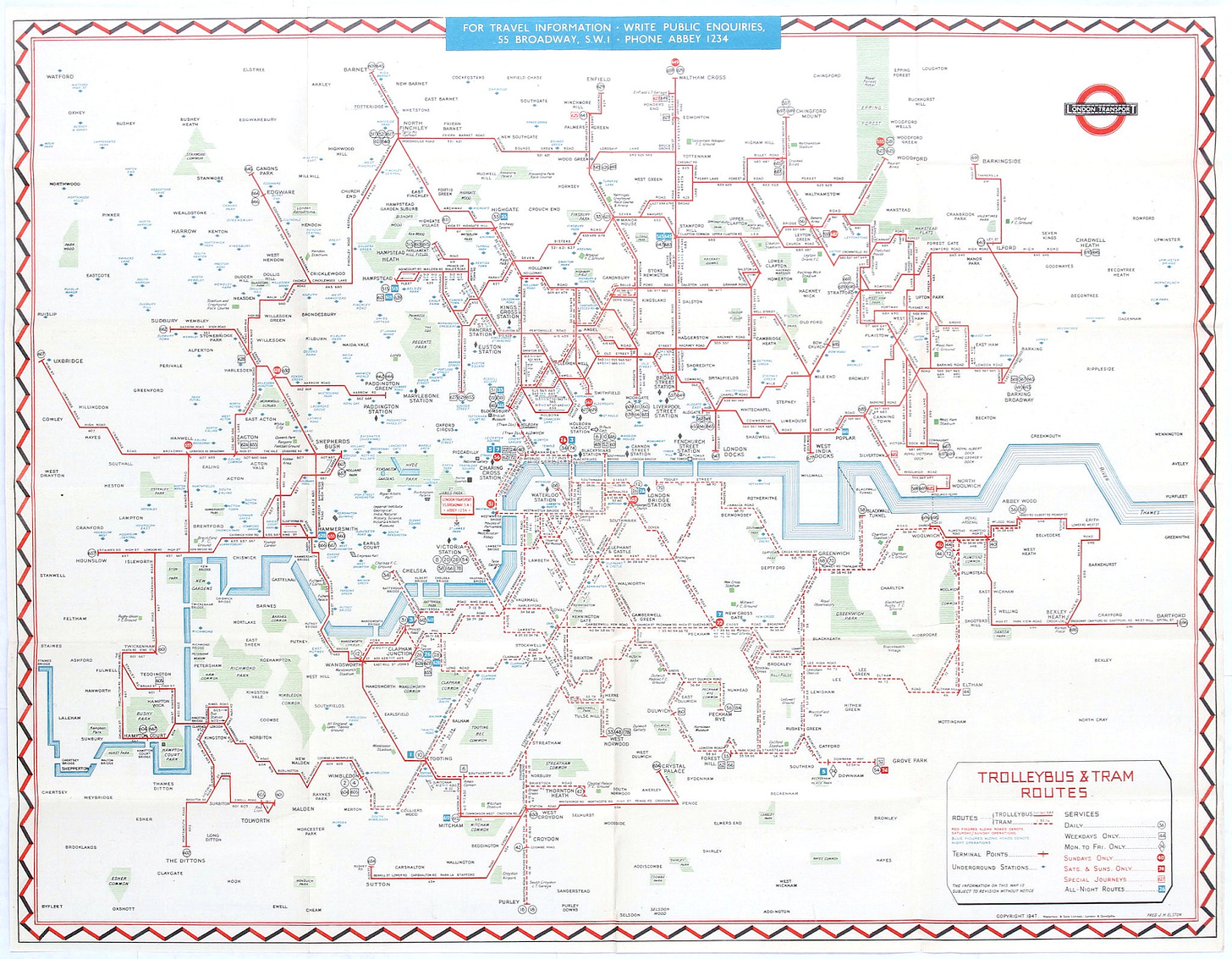

London’s history is littered with examples of where local NIMBYs held back progress. Before it had such reliable tube networks the trolleybus and trams were even more important for London’s commuters. But for years the West End and the City of London refused to have the routes run through the centre, only up to it from suburban areas, to cut down on noise and disruption. Imagine how much less convenient that would be if you were trying to cut through central London on public transport. Eventually they relented, a victory for the whole of London over the interests of specific central areas.

Trolleybus and tram routes, 1947

The Mayor should change his position and back the Soho Business Alliance, by including plans to pedestrianise Soho along with Oxford Street in the remit of the new Mayoral Development Corporation.

Soho has that magic about it, the magic that reminds us London is more than a collection of small towns around political and financial districts. It’s the world’s greatest capital city. Soho deserves better than being a cut-through for tour buses or taxis scouting for late night fares. It should be the place where people want to go – not one to just pass through.

Great read, a very similar argument could be made for Bermondsey Street.

> London is an outlier in European cities when it comes to the lack of pedestrianised zones. Barcelona’s La Rambla, the rue des Rosiers in Paris, much of Madrid, and 50 hectares of Ghent in Belgium show us what designing urban areas around pedestrians, not vehicles, can do.

Loved this quote.

I'm afraid I disagree. Pedestrianisation sanitises and sterilises a place. And the often quoted 'outlier' argument never works with me either: London is London - trying to make it like every other major city is precisely what we DON'T want. Cities are made to have thoroughfares - they are the veins and soul of a place. Trunkating thoroughfares that were built as through routes destroys historic streetscapes and replaces them with either glum or scruffy plazas - or both. Norman Foster says one of his greatest legacies is the pedestrianisation of the North of Trafalgar Square: I presume he's neither walked through the arid travesty nor driven anywhere near it of late...